America has a very stupid president 158

Joe Biden is now in his dotage. But how much dumber has his mental decline made him?

This video demonstrates that “Biden has always been a doofus”:

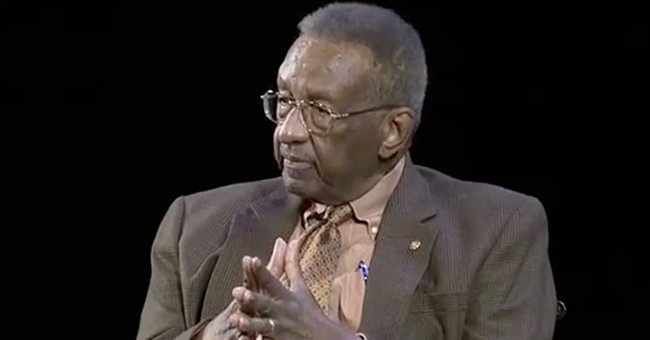

Thomas Sowell pays tribute to Walter Williams 85

We mourn the loss of Professor Walter Williams (1936-2020), a great man, a great thinker.

We looked forward to reading what another great man and great thinker, Thomas Sowell, would say about his friend Walter Williams.

Today (December 3, 2020) Thomas Sowell writes at Townhall:

Walter Williams loved teaching. Unlike too many other teachers today, he made it a point never to impose his opinions on his students. Those who read his syndicated newspaper columns know that he expressed his opinions boldly and unequivocally there. But not in the classroom.

Walter once said he hoped that, on the day he died, he would have taught a class that day. And that is just the way it was, when he died on Wednesday, December 2, 2020.

He was my best friend for half a century. There was no one I trusted more or whose integrity I respected more. Since he was younger than me, I chose him to be my literary executor, to take control of my books after I was gone.

But his death is a reminder that no one really has anything to say about such things.

As an economist, Walter Williams never got the credit he deserved. His book Race and Economics is a must-read introduction to the subject. Amazon has it ranked 5th in sales among civil rights books, 9 years after it was published.

Another book of his, on the effects of economics under the white supremacist apartheid regime in South Africa, was titled South Africa’s War Against Capitalism. He went to South Africa to study the situation directly. Many of the things he brought out have implications for racial discrimination in other places around the world.

I have had many occasions to cite Walter Williams’ research in my own books. Most of what others say about higher prices in low income neighborhoods today has not yet caught up to what Walter said in his doctoral dissertation decades ago.

Despite his opposition to the welfare state, as something doing more harm than good, Walter was privately very generous with both his money and his time in helping others.

He figured he had a right to do whatever he wanted to with his own money, but that politicians had no right to take his money to give away, in order to get votes.

In a letter dated March 3, 1975, Walter said: “Sometimes it is a very lonely struggle trying to help our people, particularly the ones who do not realize that help is needed.”

In the same letter, he mentioned a certain hospital which “has an all but written policy of prohibiting the flunking of black medical students”.

Not long after this, a professor at a prestigious medical school revealed that black students there were given passing grades without having met the standards applied to other students. He warned that trusting patients would pay — some with their lives — for such irresponsible double standards. That has in fact happened.

As a person, Walter Williams was unique. I have heard of no one else being described as being “like Walter Williams”.

Holding a black belt in karate, Walter was a tough customer. One night three men jumped him — and two of those men ended up in a hospital.

The other side of Walter came out in relation to his wife, Connie. She helped put him through graduate school — and after he received his Ph.D., she never had to work again, not even to fix his breakfast.

Walter liked to go to his job at 4:30 AM. He was the only person who had no problem finding a parking space on the street in downtown Washington. Around 9 o’clock or so, Connie — now awake — would phone Walter and they would greet each other tenderly for the day.

We may not see his like again. And that is our loss.

Betrayal 40

In general we are pessimists. (Our pessimism is made bearable, however, by laughter.) We have a view of human nature fitting what Thomas Sowell calls the “tragic vision”, which, he observes, underlies the conservative cast of mind. But we do have times when we allow ourselves optimism. As now, when we forecast a big win for President Trump in the forthcoming election.

So we do not believe that the gloomy predictions of the writer we quote below – though we agree that he makes an accurate depiction of what our enemies aim to do – will actually happen. But we share his sense of frustration that the Durham Report – expected by Trump supporters with as much eagerness as Christians expect a “Second Coming” or “The Rapture” – is being deliberately withheld from the electorate now, when it is most urgently needed. Its information concerning the attempt the Democrats made to destroy the presidency of Donald Trump belongs to the electorate and is vital to the choice that voters must make.

Chris Farrell writes at Gatestone:

Attorney General William Barr is on a Capitol Hill whispering campaign to select Republicans, telling them that US Attorney John Durham will not move against the anti-Trump coup plotters before election day. One wonders if he has bothered to tell President Donald J. Trump. The consequences for the republic are dire. We slide ever closer to being a failed state. When the justice system is compromised – and it is – we are no better than any other banana republic.

No exaggeration. In mid-July, Obamagate indictments were overdue. It is mid-October.

The disparities in federal prosecutorial discretion and speed are astounding. Durham has been at work since May 14, 2019, and one third-stringer flunky DoJ attorney (Clinesmith) has entered a half-hearted semi-plea deal for criminally lying about Carter Page’s relationship with the CIA supposedly as a cooperating legal traveler who was debriefed on his trips to Russia.

If you are a targeted member (or even a spectator) of the Trump circle, your house is raided by the FBI with (carefully coordinated) CNN coverage; your family is humiliated in public; you are bankrupted; then indicted, tried, convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison for overdue parking tickets. That whole process takes about a month. There is some exaggeration here, but not by much. Remember: Trump was impeached over Adam Schiff’s phony Ukraine hoax in two months. …

The greatest criminal conspiracy to attack the constitution and overturn the results of a presidential election is being greeted with a yawn. The Republican Party can barely generate the energy to lift its head off the desk. “Journalists” within the news media do not report factual developments, and those who do find their Internet presence suppressed by the social media giants. …

President Trump has issued order after order for the past three years – demanding full declassification and release of all records dealing with the Hillary Clinton’s outlaw email server and the Russia Hoax. For three years, his White House staff has cheerfully answered, “Yes, sir!” – and then gone out in the hallway to rationalize and conspire towards failing to energetically and faithfully carry out the Commander-in-Chief’s orders. It is loathsome and despicable how the President has been betrayed.

Here are the consequences for the picture painted before you: we are in serious danger of the “fundamental transformation” of America that some politicians dreamed of coming to fruition:

One party is effectively saying it will pack the courts, including the Supreme Court, with politically friendly judges, so that the judiciary will be an extension of one political party rather than part of a system of checks and balances, the separation of powers or a co-equal branch of government. One party is openly saying it will remove the electoral college, so that sparsely populated, rural states would be totally outvoted by cities. One party is openly saying that it would add more states, such as Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico, to provide it with more Senators to create a permanent one-party rule. One party is openly saying it would reverse core parts of our Bill of Rights so we could be jailed for exercising our freedom of speech, or for owning a gun to defend ourselves, as the minutemen did, against “enemies foreign and domestic”.

This was the situation that brought about the downfall of Venezuela: the government confiscated guns, then people had no way of protecting themselves when the storm troopers showed up. We would have had a good run as a democratic republic – but the country will be fundamentally and permanently disfigured in a way that will make it unrecognizable. The crime and the cover-up will have been successfully completed. No scrutiny, no justice, no consequences, no memory, no country. The real shame, as in Venezuela, is that many will not even notice until it is too late.

He is right about what the consequences would be – but their coming upon us depends on a Democrat victory. Such a victory would indeed be a “serious danger”. He seems to think it might well happen. We don’t.

The release of the Durham report could ensure that it doesn’t happen.

We don’t even know why it is not being released. We need – at least – to be told why.

The case against reparations 9

It is surely true to say that no matter who you are or where you come from, you have ancestors who were slaves and ancestors who owned slaves.

That alone is an argument against the idea that, on the grounds of an ancestral debt, people living now who do not and never have owned slaves, owe reparations to other people living now who are not and never have been slaves.

Yet a number of Americans – all Democratic Socialists, in a range of skin colors, some of them male but awfully sorry about it – who want to be president of the United States, are considering a policy of paying reparations to descendants of black slaves who were brought to America from Africa.

Those who are for it do not stipulate who will pay the reparations. All American tax-payers, including the descendants of slaves? All white American tax-payers? All Americans who have some white ancestors? Or only the descendants of slave owners?

Coleman Hughes, an undergraduate philosophy student at Columbia University, has written an article at Quillette which asks all the right questions about reparations, and gives all the right answers. It is a brilliant piece of lucid argument.

Coleman Hughes

In 2014, Ta-Nehisi Coates was catapulted to intellectual stardom by a lengthy Atlantic polemic entitled The Case for Reparations. The essay was an impassioned plea for Americans to grapple with the role of slavery, Jim Crow, and redlining in the creation of the wealth gap between blacks and whites, and it provoked a wide range of reactions. Some left-wing commentators swallowed Coates’s thesis whole, while others agreed in theory but objected that reparations are not a practical answer to legitimate grievances. The Right, for the most part, rejected the case both in theory and practice.

Although the piece polarized opinion, one fact was universally agreed upon: reparations would not be entering mainstream politics anytime soon. According to Coates’s critics, there was no way that a policy so unethical and so unpopular would gain traction. According to his fans, it was not the ethics of the policy but rather the complacency of whites—specifically, their stubborn refusal to acknowledge historical racism—that prevented reparations from receiving the consideration it merited. Coates himself, as recently as 2017, lamented that the idea of reparations was “roundly dismissed as crazy” and “remained far outside the borders of American politics”.

In the past month, we’ve all been proven wrong. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris have both endorsed the idea, and House speaker Nancy Pelosi has voiced support for proposals to study the effects of historical racism and suggest ways to compensate the descendants of slaves. These people are not on the margins of American politics. Most polls have Harris and Warren sitting in third and fourth place, respectively, in the race for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, and Pelosi is two heart attacks away from the presidency.

Let me pre-empt an objection: neither Harris nor Warren has endorsed a race-specific program of reparations. Indeed Harris has made it clear that what she’s calling “reparations” is really just an income-based policy by another name. The package of policies hasn’t changed; only the label on the package has. So who cares?

In electoral politics, however, it is precisely the label that matters. Given that there’s nothing about her policies that requires Harris to slap the “reparations” label onto them, her decision to employ it suggests that it now has such positive connotations on the Left that she can’t reject the label without paying a political price. Five years ago, Coates, his fans, and his critics more or less agreed that it would be political suicide for a candidate to so much as utter the word “reparations” in an approving tone of voice. Now, we have a candidate like Harris who seems to think it’s political suicide not to. The Overton window has shifted.

In one sense, Coates should be celebrating. He, more than anyone, is responsible for the reintroduction of reparations into the public sphere. Most writers can only dream of having such influence. But in another sense, his victory is a pyrrhic one. That is, the very adoption of reparations by mainstream politicians throws doubt on the core message of Coates’s work. In his 2017 essay collection, We Were Eight Years in Power, Coates argued that racism is not merely“a tumor that could be isolated and removed from the body of America,” but “a pervasive system both native and essential to that body”; white supremacy is “so foundational to this country” that it will likely not be destroyed in this generation, the next, “or perhaps ever”; it is “a force so fundamental to America that it is difficult to imagine the country without it”.

Now ask yourself: How likely is it that a country matching Coates’s description would find itself with major presidential contenders proposing reparations for slavery, and not immediately plummeting in the polls? The challenge for Coates and his admirers, then, is to reconcile the following claims:

1. America remains a fundamentally white supremacist nation.

2. Presidential contenders are competing for the favor of a good portion of the American electorate partly by signaling how much they care about, and wish to redress, historical racism.

You can say (1) or you can say (2) but you can’t say them both at the same time without surrendering to incoherence. Coates himself has recognized this contradiction, albeit indirectly. “Why do white people like what I write?” he asked [italics in original] in We Were Eight Years in Power. He continued:

“The question would eventually overshadow the work, or maybe it would just feel like it did. Either way, there was a lesson in this: God might not save me, but neither would defiance. How do you defy a power that insists on claiming you? What does the story you tell matter, if the world is set upon hearing a different one?” [italics mine]

In Coates’s mind, the fact that so many white people love his work suggests that they do not fully understand it, that they are “hearing a different” story to the one he is telling. But a more parsimonious explanation is readily available: white progressives’ reading comprehension is fine and they genuinely love his message. This should be unsurprising since white progressives are now more “woke” than blacks themselves. For example, white progressives are significantly more likely than black people to agree that “racial discrimination is the main reason why blacks can’t get ahead”.

This presents a problem for Coates. If you believe, as he does, that the political Left “would much rather be talking about the class struggles” that appeal to “the working white masses” than “racist struggles,” then it must be jarring to realize that the very same, allegedly race-averse Left is the reason that your heavily race-themed books sit atop the New York Times bestseller list week after week. Coates’s ideology, in this sense, falls victim to its own success.

But a pyrrhic victory is a kind of victory nonetheless, and so, partly thanks to Coates, we must have the reparations debate once again.

First, a note on the framing of the debate: Virtually everyone who is against reparations is in favor of policies aimed at helping the poor. The debate, therefore, is not between reparations and doing nothing for black people, but between policy based on genealogy and policy based on socioeconomics. Accordingly, the burden on each side is not to show that its proposal is better than nothing—that would be easy. The burden on each side is to show that its preferred rationale for policy (either genealogy or socioeconomics) is better than the rationale proposed by the other side. And, framed as such, reparations for slavery is a losing argument.

For starters, an ancestral connection to slavery is a far less reliable predictor of privation than a low income. There are tens of millions of descendants of American slaves and many millions of them are doing just fine. As Kevin Williamson put it: “Some blacks are born into college-educated, well-off households, and some whites are born to heroin-addicted single mothers, and even the totality of racial crimes throughout American history does not mean that one of these things matters and one does not.”

Williamson’s observation holds not only between blacks and whites but between different black ethnic groups as well. Somali-Americans, for example, have lower per-capita incomes than native-born black Americans. Yet they would not see a dime from reparations, since they have no connection to American slavery. But should it matter why Somali immigrants are poorer than black American natives? Insofar as there is a reparations policy that would benefit the poor, should Somali immigrants be denied those benefits because they are poor for the wrong historical reasons? The idea can only be taken seriously by those who value symbolic justice for the dead over tangible justice for the living.

We can either direct resources toward the individuals who most need them, or we can direct them toward the socioeconomically-diverse members of historical victim groups. But we cannot direct the same resources in both directions at once. In 2019, “black” and “poor” are not synonyms. Every racial group in America contains millions of people who are struggling and millions of people who are not, and if any debt is owed, it is to the former.

Secondly, the case for reparations relies on the intellectually lazy assumption that the problems facing low-income blacks today are a part of the legacy of slavery. For most problems, however, the timelines don’t match up. Black teen unemployment, for instance, was virtually identical to white teen unemployment (in many years it was lower) until the mid-1950s, when, as Thomas Sowell observed in Discrimination and Disparities, successive minimum wage hikes and other macroeconomic forces artificially increased the price of unskilled labor to employers—a burden that fell hardest on black teens. Not only did problems like high youth unemployment and fatherless homes not appear in earnest until a century after the abolition of slavery, but similar patterns of social breakdown have since been observed in other groups that have no recent history of oppression to blame it on, such as the rise of single-parent homes in the white working class.

Nevertheless, there is a sense nowadays that history affects blacks to such a unique degree that it places us in a fundamentally different category from other groups. David Brooks, a New York Times columnist and a recent convert to the cause of reparations, recently explained that “while there have been many types of discrimination in our history”, the black experience is “unique and different” because it involves “a moral injury that simply isn’t there for other groups”.

I’m highly skeptical of the blacks-are-unique argument. For one thing, it’s not true that blacks have inherited psychological trauma from historical racism. Though the budding field of epigenetics is sometimes used to justify this claim, a recent New York Times article poured cold water on the hypothesis: “The research in epigenetics falls well short of demonstrating that past human cruelties affect our physiology today.” (For what it’s worth, this accords with my own experience. If there is a heritable psychological injury associated with being the descendant of slaves, I’ve yet to notice it.)

But more importantly, if humans really carried the burden of history in our psyches, then all of us, regardless of race, would be carrying very heavy burdens indeed. Although American intellectuals speak of slavery as if it were a uniquely American phenomenon, it is actually an institution that was practiced in one form or another by nearly every major society since the dawn of civilization. As the Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson wrote in his massive study, Slavery and Social Death:

‘There is nothing notably peculiar about the institution of slavery. It has existed from before the dawn of human history right down to the twentieth century, in the most primitive human societies and in the most civilized. There is no region on earth that has not at some time harbored the institution. Probably there is no group of people whose ancestors were not at one time slaves or slaveholders.”

And that’s to say nothing of the traumas of war, poverty, and starvation that would show up abundantly in all of our ancestral histories if we were to look. Unless blacks are somehow exempt from the principles governing human psychology, the mental effects of historical racism have not been passed down through the generations. Yes, in the narrow context of American history, blacks have been uniquely mistreated. But in the wider context of world history, black Americans are hardly unique and should not be treated as such.

Finally, the framing of the reparations debate presupposes that America has done nothing meaningful by way of compensation for black people. But in many ways, America has already paid reparations. True, we haven’t literally handed a check to every descendant of slaves, but many reparations proponents had less literal forms of payment in mind to begin with.

Some reparations advocates, for instance, have proposed race-conscious policies instead of cash payments. On that front, we’ve done quite a bit. Consider, as if for the first time, the fact that the U.S. college admissions system is heavily skewed in favor of black applicants and has been for decades. In 2009, the Princeton sociologist Thomas Espenshade found that Asians and whites had to score 450 and 310 SAT points higher than blacks, respectively, to have the same odds of being admitted into elite universities. (The entire test, at the time of the study, was out of 1600 points.)

Racial preferences extend into the job market as well. Last September, the New York Times reported on an ethnically South Asian television writer who “had been told on a few occasions that she lost out on jobs because the showrunner wanted a black writer.” The article passed without fanfare, probably because such racial preferences—or “diversity and inclusion” programs—pervade so many sectors of the U.S. labor market that any particular story doesn’t seem newsworthy at all.

Furthermore, many government agencies are required to allocate a higher percentage of their contracts to businesses owned by racial minorities than they otherwise would based on economic considerations alone. Such “set-aside” programs exist at the federal level as well as in at least 38 states—in Connecticut at least 25 percent of government contracts with small businesses must legally be given to a minority business enterprise (MBE), and New York has established a 30 percent target for contracts with MBEs. One indication of the size of this racial advantage is that, for decades, white business owners have been fraudulently claiming minority status, sometimes risking jail time, in order to increase their odds of capturing these lucrative government contracts. (A white man from Seattle is currently suing both the state of Washington and the federal government for rejecting his claim to own an MBE given his four percent African ancestry.)

My point is not that these race-conscious policies have repaid the debt of slavery; my point is that no policy ever could. For this reason I reject the appeasement-based case for reparations occasionally made by conservatives—namely, that we should pay reparations so that we can finally stop talking about racism once and for all. Common sense dictates that when you reward a certain behavior you tend to get more of it, not less. Reparations, therefore, would not, and could not, function as “hush money.” Reparations would instead function as a kind of subsidy for activism, an incentive for the living to continue appropriating grievances that rightfully belong to the dead.

Some reparations advocates, however, are less focused on tangible dispensations to begin with. Instead they see reparations as a spiritual or symbolic task. Coates, for example, defines reparations primarily as a “national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal” and a “full acceptance of our collective biography and its consequences”—and only secondarily as the payment of cash as compensation. How has America done on the soul-searching front? As Coates would have it, not very well. For him, the belief occupying mainstream America is that “a robbery spanning generations could somehow be ameliorated while never acknowledging the scope of the crime.”

By my lights, however, we’ve done quite a bit of symbolic acknowledging. For over 40 years we’ve dedicated the month of February to remembering black history; Martin Luther King Jr. has had a national holiday in his name for almost as long; more or less every prominent liberal arts college in the country has an African-American studies department and many have black student housing; both chambers of Congress have independently apologized for slavery and Jim Crow; and just last month the Senate passed a bill that made lynching a federal crime, despite the fact that lynching was already illegal (because it’s murder), has not been a serious problem for at least half a century, and was already the subject of a formal apology by the Senate back in 2005.

If this all amounts to nothing—that is, to a non-acknowledgement of historical racism—then I’m left wondering what would or could qualify as something. The problem with the case for spiritual reparations is its vagueness. What, precisely, is a “national reckoning” and how will we know when we’ve completed it? The trick behind such arguments, whether intentional or not, is to specify the debt owed to black Americans in just enough detail to make it sound reasonable, while at the same time describing the debt with just enough vagueness to ensure that it can never decisively be repaid.

At bottom, the reparations debate is a debate about the relationship between history and ethics, between the past and the Good. On one side are those who believe that the Good means using policy to correct for the asymmetric racial power relations that ruled America for most of its history. And on the other side are those who believe that the Good means using policy to increase human flourishing as much as possible, for as many as possible, in the present.

Both visions of the Good—the group-based vision and the individualist vision—require the payment of reparations to individuals (and/or their immediate family members) who themselves suffered atrocities at the hands of the state. I therefore strongly approve of the reparations paid to Holocaust survivors, victims of internment during World War II, and victims of the Tuskegee experiments, to name just a few examples. Where the two visions depart is on the question of whether reparations should be paid to poorly-defined groups containing millions of people whose relationship to the initial crime is several generations removed, and therefore nothing like, say, the relationship of a Holocaust survivor to the Holocaust.

Among the fallacies of the group-based vision is the conceit that we are capable of accurately assessing, and correcting for, the imbalances of history to begin with. If we can’t even manage to consistently serve justice for crimes committed between individuals in the present, it defies belief to think that we can serve justice for crimes committed between entire groups of people before living memory—to think, in other words, that we can look at the past, neatly split humanity into plaintiff groups and defendant groups, and litigate history’s largest crimes in the court of public opinion.

If we are going to have a national reckoning, it must be of a different type than the one suggested by Coates. It must be a national reckoning that uncouples the past and the Good. Such a reckoning would not entail forgetting our history, but rather liberating our sense of ethics from the shackles of our checkered past. We cannot change our history. But the possibility of a just society depends on our willingness to change how we relate to it.

Black America awakes? 24

Bill Whittle explains why a few words from Kanye West threaten the very existence of the Democratic Party:

Fairness, racism, compassion, and the hungry (repeat) 66

This article was first posted on June 27, 2012, before the worst president in American history, Barack Obama, was elected – unaccountably – for the second time. We think it bears repeating now, as the defeated Left moans on about racism in particular.

*

Cruelty and sentimentality are two sides of the same coin. Collectivist ideologies, however oppressive, justify themselves in sweet words of sharing-and-caring. Disagree with a leftie, and she will lecture you in pained tones on how a quarter of the children of America “go to bed hungry”. Or say that you are against government intervention in industry, and she’ll describe horrific industrial accidents, as if bureaucrats could prevent them from ever happening. Collectivists believe that only government can cure poverty by redistributing “the wealth”, not noticing that, if they were right, poverty would have been eliminated long ago in all the socialist states of the world – the very ones we see collapsing now, under the weight of debt.

However rich the crocodile weepers of the Left may be (and many of them are very rich and passionately devoted to redistributing other people’s wealth, such as John Kerry, Nancy Pelosi, George Soros), they are likely to tell you that they “don’t care about money”. They despise it. (“Yucks, filthy stuff! Republicans with their materialist values can think of nothing else!”) Or if they are union members, and demand ever higher wages and fatter pensions, they express the utmost contempt for the producers of wealth. To all of these, we at TAC issue a permanent invitation. If you feel burdened by the possession of wealth, we’re willing to relieve you of it. We have a soft spot for money. The harsh words said about it rouse our sincere compassion. We promise to welcome it no matter where it comes from, and give it a loving home. [No, we are not asking for donations.]

In regard to the hard Left and its sweet vocabulary, here are some quotations from a column by the great political philosopher Thomas Sowell. He writes (but sorry, the page is no longer there to link to0):

One of the most versatile terms in the political vocabulary is “fairness”. It has been used over a vast range of issues, from “fair trade” laws to the Fair Labor Standards Act. And recently we have heard that the rich don’t pay their “fair share” of taxes. … Life in general has never been even close to fair, so the pretense that the government can make it fair is a valuable and inexhaustible asset to politicians who want to expand government.

“Racism” is another term we can expect to hear a lot this election year, especially if the public opinion polls are going against President Barack Obama. Former big-time TV journalist Sam Donaldson and current fledgling CNN host Don Lemon have already proclaimed racism to be the reason for criticisms of Obama, and we can expect more and more talking heads to say the same thing as the election campaign goes on. The word “racism” is like ketchup. It can be put on practically anything — and demanding evidence makes you a “racist”.

A more positive term that is likely to be heard a lot, during election years especially, is “compassion”. But what does it mean concretely? More often than not, in practice it means a willingness to spend the taxpayers’ money in ways that will increase the spender’s chances of getting reelected. If you are skeptical — or, worse yet, critical — of this practice, then you qualify for a different political label: “mean-spirited”. A related political label is “greedy”.

In the political language of today, people who want to keep what they have earned are said to be “greedy”, while those who wish to take their earnings from them and give them to others (who will vote for them in return) show “compassion”.

A political term that had me baffled for a long time was “the hungry”. Since we all get hungry, it was not obvious to me how you single out some particular segment of the population to refer to as “the hungry”. Eventually, over the years, it finally dawned on me what the distinction was. People who make no provision to feed themselves, but expect others to provide food for them, are those whom politicians and the media refer to as “the hungry”. Those who meet this definition may have money for alcohol, drugs or even various electronic devices. And many of them are overweight. But, if they look to voluntary donations, or money taken from the taxpayers, to provide them with something to eat, then they are “the hungry”.

Beware the Compassioneers: even as they pick your pocket they try to pluck your heartstrings.

The sense of Sowell 54

At Allen West’s website, Matt Palumbo quotes just a few of the many wise sayings of Thomas Sowell, the great economist and political philosopher, who retired last year at the age of 86:

1. On taxes:

“Elections should be held on April 16th — the day after we pay our income taxes. That is one of the few things that might discourage politicians from being big spenders.”

2. On Obamacare:

“If we cannot afford to pay for doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical drugs now, how can we afford to pay for doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical drugs in addition to a new federal bureaucracy to administer a government-run medical system?”

3. On welfare:

“The biggest and most deadly ‘tax’ rate on the poor comes from a loss of various welfare state benefits — food stamps, housing subsidies, and the like — if their income goes up.”

4. On social justice:

“Many years ago, there was a comic book character who could say the magic word “shazam” and turn into Captain Marvel, a character with powers like Superman’s. Today, you can say the magic word “diversity” and turn reverse discrimination into social justice.”

5. On political correctness:

“The first time I traveled across the Atlantic Ocean, as the plane flew into the skies over London, I was struck by the thought that, in these skies, a thousand British fighter pilots fought off Hitler’s air force and saved both Britain and Western civilization. But how many students today will have any idea of such things, with history being neglected in favor of politically correct rhetoric?”

6. On liberals in academia:

“The most fundamental fact about the ideas of the political Left is that they do not work. Therefore, we should not be surprised to find the Left concentrated in institutions where ideas do not have to work in order to survive.”

7. On higher education:

“When words trump facts, you can believe anything. And the liberal groupthink taught in our schools and colleges is the path of least resistance.”

8. On diversity:

“The next time some academics tell you how important diversity is, ask how many Republicans there are in their sociology department.”

9. On the rule of law:

“A generation that jumps to conclusions on the basis of its own emotions, or succumbs to the passions or rhetoric of others, deserves to lose the freedom that depends on the rule of law. Unfortunately, what they say and what they do can lose everyone’s freedom, including the freedom of generations yet unborn.”

10. On truth:

“When you want to help people, you tell them the truth. When you want to help yourself, you tell them what they want to hear.”

11. A farewell note:

“We cannot return to the past, even if we wanted to, but let us hope that we can learn something from the past to make for a better present and future.”

Thus spake Thomas Sowell 7

Thomas Sowell is one of the (rare) great thinkers of our time.

The Daily Caller reports:

Economist and conservative public intellectual Thomas Sowell announced his retirement in his final column Tuesday.

“Even the best things come to an end. After enjoying a quarter of a century of writing this column for Creators Syndicate, I have decided to stop. Age 86 is well past the usual retirement age, so the question is not why I am quitting, but why I kept at it so long,” Sowell wrote.

Fifty quotations follow. We relish them all – and emphasize our favorites:

“If you have always believed that everyone should play by the same rules and be judged by the same standards, that would have gotten you labeled a radical 60 years ago, a liberal 30 years ago and a racist today.”

“It is amazing that people who think we cannot afford to pay for doctors, hospitals, and medication somehow think that we can afford to pay for doctors, hospitals, medication and a government bureaucracy to administer it.”

“The biggest and most deadly ‘tax’ rate on the poor comes from a loss of various welfare state benefits — food stamps, housing subsidies and the like — if their income goes up.”

“The real minimum wage is zero.”

“Elections should be held on April 16th — the day after we pay our income taxes. That is one of the few things that might discourage politicians from being big spenders.”

“The black family survived centuries of slavery and generations of Jim Crow, but it has disintegrated in the wake of the liberals’ expansion of the welfare state.”

“Helping those who have been struck by unforeseeable misfortunes is fundamentally different from making dependency a way of life.”

“The most fundamental fact about the ideas of the political left is that they do not work. Therefore we should not be surprised to find the left concentrated in institutions where ideas do not have to work in order to survive.”

“The next time some academics tell you how important diversity is, ask how many Republicans there are in their sociology department.”

“The more people who are dependent on government handouts, the more votes the left can depend on for an ever-expanding welfare state.”

“I have never understood why it is ‘greed’ to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else’s money.”

“When you want to help people, you tell them the truth. When you want to help yourself, you tell them what they want to hear.”

“It’s amazing how much panic one honest man can spread among a multitude of hypocrites. ”

“People who pride themselves on their ‘complexity’ and deride others for being ‘simplistic’ should realize that the truth is often not very complicated. What gets complex is evading the truth.”

“Much of the social history of the Western world over the past three decades has involved replacing what worked with what sounded good.”

“The first lesson of economics is scarcity: There is never enough of anything to satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics.”

“Some of the biggest cases of mistaken identity are among intellectuals who have trouble remembering that they are not God.”

“Racism does not have a good track record. It’s been tried out for a long time and you’d think by now we’d want to put an end to it instead of putting it under new management.”

“Despite a voluminous and often fervent literature on ‘income distribution’, the cold fact is that most income is not distributed: It is earned.”

“The fact that the market is not doing what we wish it would do is no reason to automatically assume that the government would do better.”

“The problem isn’t that Johnny can’t read. The problem isn’t even that Johnny can’t think. The problem is that Johnny doesn’t know what thinking is; he confuses it with feeling.”

“Socialism is a wonderful idea. It is only as a reality that it has been disastrous. Among people of every race, color, and creed, all around the world, socialism has led to hunger in countries that used to have surplus food to export. … Nevertheless, for many of those who deal primarily in ideas, socialism remains an attractive idea — in fact, seductive. Its every failure is explained away as due to the inadequacies of particular leaders. ”

“Intellect is not wisdom.”

“The old are not really smarter than the young, in terms of sheer brainpower. It is just that we have already made the kinds of mistakes that the young are about to make, and we have already suffered the consequences that the young are going to suffer if they disregard the record of the past.”

“Bailing out people who made ill-advised mortgages makes no more sense than bailing out people who lost their life savings in Las Vegas casinos.”

“Freedom has cost too much blood and agony to be relinquished at the cheap price of rhetoric.”

“There are only two ways of telling the complete truth – anonymously and posthumously.”

“Socialism in general has a record of failure so blatant that only an intellectual could ignore or evade it.”

“Can you cite one speck of hard evidence of the benefits of ‘diversity’ that we have heard gushed about for years? Evidence of its harm can be seen — written in blood — from Iraq to India, from Serbia to Sudan, from Fiji to the Philippines. It is scary how easily so many people can be brainwashed by sheer repetition of a word.”

“Since this is an era when many people are concerned about ‘fairness’ and ‘social justice,’ what is your ‘fair share’ of what someone else has worked for?”

“Unfortunately, the real minimum wage is always zero, regardless of the laws, and that is the wage that many workers receive in the wake of the creation or escalation of a government-mandated minimum wage, because they lose their jobs or fail to find jobs when they enter the labor force. Making it illegal to pay less than a given amount does not make a worker’s productivity worth that amount—and, if it is not, that worker is unlikely to be employed.”

“Competition does a much more effective job than government at protecting consumers.”

“The most basic question is not what is best, but who shall decide what is best.”

“What sense would it make to classify a man as handicapped because he is in a wheelchair today, if he is expected to be walking again in a month, and competing in track meets before the year is out? Yet Americans are generally given ‘class’ labels on the basis of their transient location in the income stream. If most Americans do not stay in the same broad income bracket for even a decade, their repeatedly changing ‘class’ makes class itself a nebulous concept. Yet the intelligentsia are habituated, if not addicted, to seeing the world in class terms.”

“Rhetoric is no substitute for reality.”

“Virtually no idea is too ridiculous to be accepted, even by very intelligent and highly educated people, if it provides a way for them to feel special and important. Some confuse that feeling with idealism.”

“What is history but the story of how politicians have squandered the blood and treasure of the human race?”

“If politicians stopped meddling with things they don’t understand, there would be a more drastic reduction in the size of government than anyone in either party advocates.”

“One of the consequences of such notions as ‘entitlements’ is that people who have contributed nothing to society feel that society owes them something, apparently just for being nice enough to grace us with their presence.”

“Economics is a study of cause-and-effect relationships in an economy. It’s purpose is to discern the consequences of various ways of allocating resources which have alternative uses. It has nothing to say about philosophy or values, anymore than it has to say about music or literature.”

“Whenever someone refers to me as someone ‘who happens to be black’, I wonder if they realize that both my parents are black. If I had turned out to be Scandinavian or Chinese, people would have wondered what was going on.”

“Don’t you get tired of seeing so many ‘non-conformists’ with the same non-conformist look?”

“If you have been voting for politicians who promise to give you goodies at someone else’s expense, then you have no right to complain when they take your money and give it to someone else, including themselves.”

“Life does not ask what we want. It presents us with options.”

‘It doesn’t matter how smart you are unless you stop and think.”

“Everyone may be called ‘comrade’, but some comrades have the power of life and death over other comrades.”

“If you are not prepared to use force to defend civilization, then be prepared to accept barbarism.”

“People who have time on their hands will inevitably waste the time of people who have work to do.”

“In an age of artificial intelligence, too many of our schools and colleges are producing artificial stupidity.”

“Many on the political left are so entranced by the beauty of their vision that they cannot see the ugly reality they are creating in the real world.”

These sayings are a small part of a rich gift to the world. There is much more of his wisdom to be found in his books.

Here Thomas Sowell talks about “global warming”: